In its first full year of business in 1998, the 99 Cents Only store in the north Los Angeles city of Lancaster did over $5 million in sales. This was welcome news to the city, given the space had been vacant ever since the new “Power Center” shopping development, where 99 Cents was located, opened ten years earlier. Almost immediately, however, 99 Cents’ next door neighbor, Costco, told the city it needed to expand. The owner of the center offered Costco optimal space behind 99 Cents, but Costco insisted that the city use its power of eminent domain to condemn 99 Cents’ business. If the city refused, Costco threatened to relocate to neighboring Palmdale, who surely would use every tool at its disposal to attract the lucrative big box store’s business. To seal the deal, Costco issued an additional threat: not only would it relocate to Palmdale—it would leave its existing store shuttered and vacant as an economic deadweight on the city’s key commercial center. Backed against the wall, the terrified city relented. It condemned 99 Cents’ store, paid the shopping center owner $3.8 million, and gave the parcel to Costco for one dollar.

This story typifies what drives all rent-seeking: Motive and opportunity. Businesses seek economic advantage wherever they can find it, and they frequently find it in the coercive power of the state. Ill-defined limits on government powers—of which eminent domain is just one example—give businesses easy access to this power. When the economy grows, the motive to capture the government intensifies. When government is centralized, the opportunities to capture it get cheaper and more convenient. When the limits on government recede, these opportunities get still cheaper and more abundant. Motive explains why rational private interests engage in rent-seeking: to gain a competitive edge. Opportunity—that is, the opportunity for access to government power through ill-defined limits on that power—explains why rational government officials yield to special interests: they face a “race to the bottom.” If the Lancasters of the world refuse to use their coercive government power for the benefit of special interests, some other government official or agency will. Denying access to special interests just means they will look elsewhere. And they will surely find it, so long as giving in to special interests is a matter of legislative “discretion.”

Motive and opportunity answers the problem of political corruption at the heart of Lawrence Lessig’s new book, Republic, Lost: How Money Corrupts Congress—and a Plan to Stop It. Corruption, for Lessig, is not limited to vile, money-in-the-briefcase, quid pro quo corruption. The kind of corruption destroying American politics is systemic, in which ordinary people—both those in power and those seeking access to it—respond logically to powerful incentives. The opportunity for access to influence in the increasingly centralized federal government is overwhelming. This access has caused trust in government to reach an all-time low. Just 12% of Americans in 2008 had confidence in Congress, falling to 11% midway through Obama’s presidency. According to Lessig’s own poll, a staggering 75% believe “campaign contributions buy results in Congress.”

The distrust is justified according to Lessig by looking at the dramatic recent increase in campaign contributions. From 1974 to 2008, the average Congressional reelection campaign surged from $56,000 to over $1.3 million. The total spent by all candidates in the eight years prior to 1982 increased 450%. By 2010, it spiked another 525% to $1.8 billion. The financial sector alone spent $1.7 billion in campaign contributions and $3.4 billion in lobbying expenses between 1998 and 2008. The contributions of just 100 financial firms since 1989 total more than those of the entire energy, health care, defense, and telecom industries combined.

The motive for all this lobbying? Access to power over a national economy that, over the past 70 years, has been increasingly centralized in a single legislature—i.e., Congress. Henry Manne recognized in 1966 that “the federal government is the largest producer of information capable of having a substantial effect on stock-market prices.” According to University of Kansas researchers, every dollar spent on lobbying in D.C. returns between $6 and $20. The effectiveness of these dollars increases exponentially for major firms. After about $800,000, an additional 1% in lobbying produces tax benefits between $4.8 and $16 million—a 600% to 2,000% return. Rational economic actors are hard pressed to find better opportunity to advance their motive. This explains why, from 1971 to 1981, the number of registered lobbying firms in D.C. jumped from 175 to almost 2,500, and to 13,700 by 2009. These firms spend about $6.5 million per federal legislator per year. These lobbyists and the special interests they represent follow the model of Tammany Hall boss George Washington Plunkitt who, in explaining his self-styled “honest graft,” said “I might sum up the whole thing by saying: ‘I seen opportunities and I took ’em.'”

A national economy governed by a single, centralized government, offers a rich variety of opportunities to access the levers of power. Lessig offers corn subsidies as an example. High-fructose corn syrup, a new invention in 1980, enjoyed a 35% share of sugar consumption in the U.S. just five years later, and a 41% share by 2006. Not that the stuff is actually profitable. Lessig notes that “every $1 of profits earned by ADM’s corn sweetener operation costs consumers $10, and every $1 of profits earned by its ethanol operation costs taxpayers $30.” This is due to high tariffs that keep competition largely limited to eight manufacturers who receive $1 billion in extra profits from the tariffs at a cost of about $3 billion to consumers.

These policies lead to freakonomics-style unintended consequences: In addition to hurting legitimate American businesses, consumers, and developing nations, federal corn subsidies and cane tariffs contribute to the proliferation of drug-resistant suberbugs like E. coli and salmonella. Cows and their seven stomachs are evolved to digest grass. By contrast, corn digests poorly, giving bugs time to brew, making the cows sick. In response, farmers supplement the cows’ corn diet with tons of antibiotics—25 million pounds every year, eight times the amount consumed by humans. Because corn is so heavily subsidized by the federal government, however, corn feed plus 25 million pounds of drugs still costs less than grass. This proliferation of antibiotics among cows, and passed up the food chain to us, fosters stronger, antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

The federal government extends similar subsidies and protections to the dairy industry. Price setting and other regulations increase the price consumers pay for milk by 26%, cheese by 37%, and butter by 100%. Again, the principal recipients of these subsidies are those farms with the greatest access to influence: 10% of the recipients of farm subsidies collect 73% of the subsidies, while the bottom 80% take just $3,000 each on average.

At one level, none of this ought to be surprising. Special interests are nothing new, and Lessig acknowledges that the warped influence of special interests on government was “the single most important corruption that the Framers were working to cure.” Nor can we reasonably claim surprise at the effects of wealth on politics. A hundred years ago, prominent statesman Elihu Root observed that as population and wealth increased, so would rent-seeking: “[P]olitical organizations controlled the operations of government, in accordance with the wishes of the managers of the great corporations. Under these circumstances our governmental institutions were not working as they were intended to work, and a desire to break up and get away from this extra constitutional method of controlling our constitutional government has caused a great part of the new political methods of the last few years.” Teddy Roosevelt concurred: “Corporate expenditures for political purposes… have supplied one of the principal sources of corruption in our political affairs.”

At another level, however, we have reason to suspect we are suffering more injury from special interests and crony capitalism than we have a right to. Had the Constitution’s limits on federal and state government power survived the 20th century, special interests simply would not have the opportunities they have today to capture government influence. Consider the nature of the opportunity that gave Costco access to Lancaster’s eminent domain power. It wasn’t money: the Constitution did not subject protection of private property to a highest-bidder qualification. It wasn’t cronyism: Lancaster officials, caught in the crossfire between rent-seeker and the awesome authority to decide the fate of private property, did everything it could to dissuade Costco and keep both stores. Instead, the cause was ill-defined limits on governmental power. As a result of a series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions (culminating in Kelo v. City of New London a few years later in 2005), Lancaster was empowered—ironically, to its own detriment—to wield the eminent domain power subject to its own discretion and effectively without judicial oversight. This created opportunity for Costco to pit one city against another to demolish its competition, all removed from the actual marketplace. Though a federal district court in 2001 invalidated Lancaster’s transfer, Kelo upheld a similar transfer four years later.

The supply of influence is increased when limits on government authority are eroded or ill-defined. This opens the floodgates of money into politics, largely in the form of independent expenditures from rational rent-seekers. Regardless of whether this results in actual buying-and-selling of votes, the more certain and more disastrous result is the erosion of legitimacy in our democratic institutions: the individual sees his voice and political contributions drowned out by special interests with motive and opportunity to conscript lawmakers into their service.

Murray Kane, a Los Angeles redevelopment lawyer who helps cities take property for government projects, is perhaps an unlikely critic of ill-defined government power, at least when it comes to eminent domain. Yet, in 1995 Mr. Kane challenged the city of Diamond Bar when it similarly extended that power as an opportunity to serve private motives. Even though his clients benefit from eminent domain, Mr. Kane warned that eroding its limits would result in “a legislative backlash.” That backlash “could go beyond stopping redevelopment abuse, and will also hurt redevelopment in truly blighted areas where redevelopment is really needed.” Power exercised never fails to instill fear. It engenders trust only when its exercise is limited, and only so long as those limits are honored.

Members of Congress have not gleaned this lesson. Lessig explains how federal legislators increase the opportunity for special interests to extort rents from government—”[i]ncreasing ‘extortion’-inducing ‘rents’ produces only one thing: more extortion!” Our leaders seemed to have understood this at one time. Lessig recalls that 30 ago, Senator John Stennis, chairman of the Armed Services Committee, balked at hosting defense contractors at a fundraiser. “Would that be proper?” Stennis asked. “I hold life and death over those companies. I don’t think it would be proper for me to take money from them.” By 2006, however, Senator Chuck Hagel observed that “We’ve blown past the ethical standards, we now play on the edge of the legal standards.”

In his new book, Throw Them All Out, Peter Schweizer argues that the only reason politicians have not blown past legal standards as well is because, as the ones who write the legal standards, they’ve made themselves exempt. Congress imposes conflict-of-interest rules on everyone in the executive and judicial branches of the federal government. But Schweizer reports that the House’s 400-page ethics manual and the Senate’s 500 page manual “are silent on the matter of inside trading” when it comes to Congress. He provides example after example of members of Congress, both Republican and Democrat, who engage in substantial stock trading at the same time they negotiate pending legislation concerning the very companies whose stock they trade. In the private sector, we call this insider trading. When Nancy Pelosi heavily invested in natural gas IPOs at the same time she championed federal legislation favoring the development of natural gas, she told Tom Brokaw, “That’s the marketplace.” In the real marketplace, however, the average American investor underperforms the market. The average corporate insider trading his own company’s stock and the average hedge fund outperforms the market by about 7%. The average U.S. senator, however, outdoes them all, beating the market by a stunning 12%. When Washington insiders talk about “the marketplace,” then, they’re speaking a different language.

Oddly, Lessig is reluctant to dole out blame for legislators’ perverse motives. Yielding to special interests “isn’t selling out,” he reasons. “It is surviving.” Congress passes laws with “sunset” provisions and “tax extenders” in order to drum up donations from laws’ supporters when expiration draws near. “For every time a ‘targeted tax benefit’ is about to expire,” Lessig explains, “those who receive this benefit have an extraordinarily strong incentive to fight to keep it.” Lessig notes that in the 1990s, there were fewer than a dozen tax extenders in the U.S. tax code. Now there are more than 140. Because the average legislator cannot stand up to special interests and still draw enough contributions for the next reelection campaign, Lessig contends, can we really blame them for playing along?

But the dog wags his own tail, too. Schweizer describes how members of Congress use “juicer bills” or “milker bills” to extort campaign contributions and favors from businesses and individuals. For example, Schweizer recalls that in 2006, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid “announced that he wanted a tax hike on hedge funds,” and the following January, after Democrats captured both houses, “Senator Charles Schumer sat down to dinner with a number of top hedge fund managers” whose net worth totaled more than $100 billion. According to the New York Times, hedge funds were not significantly involved in lobbying or campaign spending until that time—typically well less than $2 million per year. After being “juiced” by Senators Reid and Schumer, however, hedge funds more than tripled their lobbying and campaign spending, clocking in at more than $6 million in 2007 and more than $7 million in 2008.

Legislators also deliberately create rents by limiting entry to economic activity, granting monopolies, restricting corporate charters, imposing tariffs, quotas, and regulations, and so on. By creating these rents, legislators form coalitions with rent-seekers who express their support through campaign contributions. This crony capitalism—not partisan politics or rigid ideology—explains American political dysfunction. “Our tax system is an abysmal inefficient mess not because of idiots at the IRS or on the Joint Committee on Taxation,” Lessig explains, “but because crony capitalists pay top dollar to distort the system to their benefit.” For the same reason, real financial reform remains out of reach so long as the government remains invested in protecting bloated banks. And real health care reform was impossible where “insurance companies and pharmaceutical companies had the power to veto any real change to the insanely inefficient status quo.”

Notably, Lessig expresses a brutal indignation for one politician who vowed, more earnestly and persuasively than any other in recent memory, to confront the breach of trust in Washington. This message earned space on millions of Americans’ bumpers and carried on the lips of many otherwise jaded young people. Now on the back nine of his term, Obama is “an opportunity missed”; “a bad joke”; “the last straw”; and, worst of all, “conventional.” As a further insult, Democrats have been aped by the Tea Party as the vehicle of true reform. “Earmarks were blocked in the 2011 budget because the Tea Party insisted upon it,” Lessig concedes. “There is an Office of Congressional Ethics, the only independent watchdog ensuring that members live up to the ethical rules, because the Tea Party insisted upon it.” To Lessig’s chagrin, this is not a message his compatriots on the left are ready to hear.

The motive and opportunity problem is structural. The motives of special interests are not problematic because they are illegal or unethical (though they are immoral). They are problematic because they are based in human nature and thus intractable. Just as water always flows downhill, the motives of special interests will always flow toward rational self-interest. These motives become problematic where the opportunities to promote self-interest are procedurally unjust. Blaming special interests or self-interest for the corruption in American politics makes no more sense than blaming the rain for a leaky roof. The solution in both instances is structural: Fix the structure so as to prevent the intractable force of nature from flowing where it does not belong. In the case of special interests, this means ensuring political opportunities are procedurally fair by breaking up concentrations of political power and carefully constraining government’s power over economic transactions.

Concentrations of power draw special interests into politics. The larger the concentration of power, the more overwhelming the demand. When the average legislator represents a relatively small number of constituents and a relatively small share of the economy—i.e., where the concentration of power is low—rents tend to decrease. Like any other valuable resource, political power responds to supply and demand.

Consider the nature of the “supply” of power in D.C. Congress’s 535 members wield power over more than 300 million Americans—including their wealth-producing activity. Responsible for 30 volumes and 6,200 pages of statutes, and regulations consuming over 25 feet of shelf space, Congress presides over an annual economy well over $14 trillion. The average member of Congress wields power over a share of population of about 573,000 people, and a share of GDP worth more than $27 billion. Little surprise, then, that in 2010—the year the Supreme Court held in Citizens United that corporations had the same right to make independent campaign expenditures as individuals—independent expenditures tripled from 2006 to over $210 million. Focusing on the right to participate in the political process misses the point: it’s the incentives that matter.

Devolving basic governmental functions back to the states would go a long way toward breaking up the dangerous concentration of centralized power and curbing the destructive incentive to rent-seek. For example, Alaska—one of the 10 states for which independent expenditure data has been collected—is substantially more democratic than Congress. Alaska legislators represent on average fewer than 12,000 people and a share of about $760 million of the state’s total annual GDP. Iowa’s legislature is also relatively democratic: each state legislator represents about 20,000 people and about $980 million of GDP. Even less democratic states seem Athenian when compared to D.C. A vote in the state capital speaks for 43,000 people and $1.9 billion in Wisconsin; 45,000 and $2.4 billion in Washington; 50,000 and $2.6 billion in Colorado; 67,000 and $2.5 billion in Michigan; 71,000 and $2.9 billion in Arizona; and 117,000 and $4.7 billion in Florida. Special interest dollars invested in these states thus get substantially less mileage in these states than in D.C.

Conversely, the most undemocratic state in the union, California, fares even worse than D.C. in terms of political rent-seeking. Heavily concentrated Sacramento governs both the nation’s largest population and largest economy, yet has the 16th smallest legislature: The average vote purports to speak for a staggering 310,000 people and a $16 billion share of GDP.

These numbers matter when stacked up against independent political expenditure dollars. In 2010, independent expenditures in Alaska were less than $4 million—about $62,000 per legislator. In Iowa, the number is even more modest at about $40,000 per legislator. In power-concentrated Sacramento, by contrast, independent expenditure dollars flood in at a rate of more than $1 million per legislator. Note that in the chart below, the states are arranged left-to-right according to the population per legislator (per the graph above):

Rent-seeking thus becomes more aggressive where political institutions are less democratic. The centralization of power in legislatures like those in D.C., California, and Florida empowers lobbying and campaign dollars and creates influence-buying opportunities too good for special interests to pass up.

Rent-seeking opportunities are also tightly correlated with activist regulatory policy. In June 2011, George Mason University’s Mercatus Center published its Index of Personal and Economic Freedom, ranking the 50 states according to the impact of their respective regulatory landscapes. States with pervasive labor regulations, health-insurance coverage mandates, strict occupational licensing requirements, weak limits on eminent domain, and other negative impacts on economic liberty and property rights are given a lower score on the index. The rankings are indicated in the graph as follows:

Rent-seeking tracks regulatory intensity. This is not an indictment of the merits of the regulations, of course. For purposes of the exercise, we can assume that the regulatory landscapes of Florida, Colorado, Alaska, and California—the states with both the highest reported independent expenditures per capita and among the least regulatory freedom—were crafted with scrupulous dedication to the public interest. But it is special interests’ motives, not the lawmakers’, that matter. Again, Lancaster had no desire to condemn 99 Cents. Yet this did not deter Costco from leveraging ill-defined government power against it. And recall the political game Lessig describes that legislators must play: simplifying the law, removing tax extenders, and other measures in the public interest deprive politicians from much needed fundraising opportunities.

Similarly, there is no reason to assume the New Deal’s massive expansion of government programs was the result of anything but good intentions. This does not change the fact that, as Peter Schweizer points out, the Export-Import Bank is now known as “Boeing’s Bank,” devoting almost 40% of its entire $21 billion annual business in 2008 alone to that single special interest. We could also stipulate that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the EPA are charged with important work. Not that this matters to special interests. According to Schweizer, “states with House members on the budget oversight subcommittee responsible for funding the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Environmental Protection Agency had significantly fewer listings than other states,” and “‘Congressional representatives who sit on the Interior subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee use their position to shield their constituents, at least partially, from the adverse consequences of ESA.'” Similarly, according to one study, “the IRS actually shifts enforcement away from congressional districts represented by legislators who sit on committees with oversight of the IRS.”

Centralization makes our democratic institutions less democratic, making fewer representatives responsible for the fate of greater shares of the economy and the population. This decline makes it easier for special interests to buy influence. The pressures of this influence lead lawmakers to engage in policymaking designed as much to elicit campaign dollars as to benefit the public. This conflicted-interest policymaking results in more opportunities for rent-seekers to buy or extract further political influence. Decentralization of federal power and returning governance to states and local governments will increase the democratic function of legislative institutions and make it more difficult and expensive to buy influence. States like California and Florida with poor democratic representation can increase the number of state legislators to make rent-seeking a more expensive proposition. These measures would substantially dry up opportunities for crony capitalism, and direct special interests’ profit motive to the marketplace where it belongs.

Regulatory reform, on the other hand, can only be achieved by the courts restoring the original understanding with respect to economic liberty. Even assuming pure motives on the part of a state legislature, the very fact that courts defer to its judgment on matters of economic and property rights creates opportunity for special interests to achieve their profit-driven motives through political influence rather than the market.

Modern movements demanding more government action in response to concentrations of wealth get the problem exactly backwards. Corruption and cronyism are fundamentally the result of concentrations of political power, which give special interests inexpensive one-stop shopping. For this reason did Montesquieu approvingly observe that the separation of government powers “should naturally form a state of repose or inaction.” Every act and agency of government taxes the people not only of their property and freedom, but of their trust in their democratic institutions. We must ask, then, whether the progressive new business government is charged to conduct is worth the increased corruption that will be transacted through the back door.

It is a tragic irony that people look to the same entity that enables rent-seeking in the first place as if it could be trusted to fight corruption. It’s like a hospital hiring a vampire to guard the blood donation area.

IMO a more productive approach would be to simply realize that rent-seeking is theft, and treat property claims derived from it as socially void. But I’m a bomb-throwing anarchist nutjob, so what do I know…

The magnum opus makes its appearance. Don’t have time now, but I look forward to reading it.

Yet when someone suggests that too-powerful

government could be solved by limiting government power, we are told that this person thinks that road maintenance, civil order, and fire protection should be handled by private concerns…

So the most useful question is how to do we limit gov power to screw things up while having a gov powerful enough to do good things. How do we stop a local gov in Tim’s example from using ED in a bad way but still have a gov that can keep bad stuff out of the air, or have basic worker safety, etc. Pretty much everybody wants gov limited in some ways and gov to do somethings. Of course within that vague agreement we have plenty of grist for the mill. People who focus, as Tim does, on gov overreach or limiting gov tend not to speak about how we can still have a gov to do the things it “needs” to do and vice versa.

In the case of Eminent Domain specifically, there are two changes (both used in New Zealand) that could assist matters:

1) Construing “public purpose” more narrowly.

2) Including an off-back rule so that if the government sells eminent domain property, they have to give the previous owner the right of first refusal.

That leaves you with an eminent domain that can still be used for legitimate public purposes, but is a lot less useful as a tool of rent-seeking.

Interesting point.

James,

I wish I had known about New Zealand’s off-back rule when I published my law review article outlining another approach, similar in theory, that ought to be adopted in the U.S. I suggested that instead of paying the landowner “fair market value” for the seized parcel if the parcel was to be used for private development, he should be paid on a restitutionary basis. That is, if the parcel was worth only $100,000 as a residential parcel but $250,000 as a newly-zoned commercial parcel, the owner should get the benefit of that deal struck between the city and the developer, rather than being cashed out on the cheap.

Not every state in the U.S. has the same eminent domain setup.

I like Tim’s $0.02, particularly if the city is going to adjust a parcel’s zoning.

Great points Greg (and awesome OP Tim),

I agree that a government specifically limited to those tasks it is best able to perform (such as defense and courts) is worthwhile. My recommendations would be a mix and match of the following:

Limited government

Subsidiarity

Allow competitive markets to work wherever they can

More freedom, options and choice built into the system (retire earlier at higher SS rates, or later at lower rates, etc)

Sunset provisions on regulations with increasing supermajority requirements over time

A demand for simple, consistent rules and a resistance to activist regulations that establish a dynamic of zero sum rule wrestling and rent seeking.

General economic literacy so people stop demanding the “vampires run the blood bank”

These will probably just delay the inevitable decay and corruption of society. Eventually incumbents and rent seekers and exploiters will probably win out. The other necessary element is fresh new green fields. Institutions decay and become sclerotic and cancerous just like living things. I believe we need to be actively creating new societies, markets and institutions, or we will be forced to create them out of the ashes of the old.

Delightfully depressing points, Roger.

A well written post, but to sum it up, Tim makes the familiar case that smaller government denies private power the tools it needs to deprive the people of liberty.

Which is completely true, except for the fact that private power wants government large enough to serve their interest.

As with the opening example of the City of Lancaster- Suppose the City were actualy a model of “limited government”, and lacked the power to deprive 99 Cent stores of their liberty and property rights.

Wouldn’t Costco simply have put a proposition on the ballot giving the City the tools it needs to do exactly that?

In other words, the City was being used as the servant of the private interest; yet your suggestion is to disarm the servant, and leave the master untouched?

Concentration of power- in and of itself- is the threat to liberty and democracy, and should be fought and broken up, regardless of where it occurs, private or public.

There are other ways that could be done of course, in ways that don’t involve government.

You can pay local utilities to cut off service to the 99 cent store, owners and employees.

You can create a cartel of local businesses to ban any employee of the 99 cent store from doing business locally, or make it much more difficult.

That’s just some examples…these are not new concepts to be honest, in fact they’re very old ones, just ones that we don’t see very often because of the legal blowback, more or less. Power imbalance is there, and impossible to remove. If it done via government or via other means, you’ll eventually get the powerful pushing for the same results.

And violate state law, requiring utilities to offer their services to all potential customers other than those who have demonstrated an inability to pay, in the process. Yes, that law represents a further use of the state’s power to obstruct undesired behavior. But does that make it “rent-seeking”? I think the law in this case is justified in preventing that sort of anticompetitive private behavior. So too with the cartel of businesses refusing do sell to 99-Cent store employees.

And how is that state law enforced? Via centalized government power.

To elaborate: the “preventing anticompetitive private behavior” explanation would surely seem to extend to EPA regulations and other things that Tim suggests he has complaints over. So I think the larger point still stands–whether it’s through private power or government action, concentrated wealth will seek to enrich itself at everyone’s expense, and it’s not realistic to assume that declawing the government will solve the problem.

Right, Burt. There’s also common law claims of interference with contract and economic advantage, and of course Business & Professions Code 17200 et seq.’s prohibitions on anti-competitive trade practices.

Dan

As Tim pointed out in the OP, concentrated wealth exists because of government. Breaking up the wealth does not eliminate the political power as it exists. Those who have power will just use the power they have to craft the wealth distribution to benefit them.

You can not break up wealth concentrations without first smashing the power blocks that created them.

“Suppose the City were actualy a model of “limited government”, and lacked the power to deprive 99 Cent stores of their liberty and property rights. Wouldn’t Costco simply have put a proposition on the ballot giving the City the tools it needs to do exactly that?”

Sure! Then it just has to convince the required number of citizens that it’s a good idea to legislate the 99 Cent store out of existence.

The breathtaking ease by which that can be done has been amply demonstrated many times.

Sort of like when PG&E had that ballot measure that banned municipal governments from using non-PG&E energy sources. Oh wait, that proposition got totally owned at the polls, despite the “no” side spending barely a tenth of what PG&E did on advertising.

Right. And the point has been made that we still need responsible, virtuous citizens to keep politicians at all levels of government honest. I was proud to represent such folks in Los Alamitos, when local councilmembers, who received substantial campaign contributions from a trash hauler, awarded a 10-year, $22 million contract to that same trash hauler, despite it being the 2nd highest bidder.

https://ordinary-times.com/timkowal/2011/10/17/judge-voids-los-alamitoss-illegal-trash-contract/

There’s no single solution to these problems. All the cylinders need to be firing: cultural, structural, legal, political, etc.

Wouldn’t Costco simply have put a proposition on the ballot giving the City the tools it needs to do exactly that?

In California, perhaps. But in a system with a strong constitutional impediment to such laws, and where the Constitution requires a supermajority to amend it, the odds of this happening are markedly diminished.

What is the liberals’ alternative proposal? I see much liberal condemnation of this approach as unworkable, but I don’t see much in the way of an alternative being offered.

I got through once on Dutch Courage and have some thoughts percolating but don’t have time to put them to the keyboard yet. It’s a fantastic post, just wanted to drop that in before the comment stream blows out.

What’s the R value on the “Independent Expenditures per Capita” trendline? i.e. is it full of shit or not? I’ll take non-numeric answers as a “yes, it is full of shit” And why not all 50 states?

The source of this data is linked in the OP, and pasted here for your convenience: http://www.followthemoney.org/Research/index.phtml?p=2011

These were the only states for which the data had been compiled at the time I did this research. Looks like they have a new report on Tennessee out as of 11/21.

followthemoney.org seems to be having issues this morning, but thanks for posting the source.

Neither #Occupy nor Tea Party could disagree with a word of this thinkpiece, Mr. Kowal, and that’s the beauty of it. I’m your co-blogger down here @ Dutch Courage, so my props prob don’t mean much, but WD, sir, excruciatingly well done.

Let me add a bit of local color with regards to the setup story, as it is set in my stomping grounds. The area in which the story is set consists of two large cities (Lancaster is by population the 30th largest city in California, and Palmdale is the 32nd) and they compete fiercely with one another to attract businesses for the sales tax revenue thus generated.

In the late 1990’s, the neighborhood in which the Costco was (and still is) located was thought to be a possibility for the premier site of commercial development in the 2000’s. X, Y, and Z happened along the way and most of the land around the area was not developed in the manner anticipated. There is a lot of consideration that city officials had personal stakes in investment in some of the neighboring land, and while I don’t believe any laws were broken, it stank to high heaven for a while and to this day a lot of that land is not developed as it should be. The locals want upscale commercial development there, but the market just doesn’t support it.

Meanwhile the market did support more upscale development in Palmdale. Palmdale, not Lancaster, got the Trader Joe’s and the Super Target and the competing consumer electronics stores and the Sports Chalet. Part of the reason for that was tax breaks, and part of it was demographics. The location that was intended for Costco wound up being developed by Wal-Mart and turned in to a Sam’s Club.

Don’t feel too bad for 99 Cents Only Stores, either. They have a thriving business in Lancaster still, in what for them is a good location — a quarter-square-mile large strip mall surrounded by several middle-class neighborhoods; it has two very profitable locations in Palmdale, too, again in similar kinds of areas, and in these more challenging economic times, 99 Cents Only stores have a very nice niche in the retail market.

Does it trouble anyone else how ridiculously commonplace this practice has become? I can’t even recall the last significant business move that didn’t have a subsidy attached to it.

If lefities like me talk about it, we’re insulting job creators. 🙂

Unfortunately, it’s become pretty common. Which ya’ know, then I’d talk about a race to the bottom, why this shows local government can be just as corrupt as federal government if not more so and so on, but I’ll stop there. 🙂

Ironically, the implication by the politicians who push such targeted breaks and whatnot is that markets are hopelessly fragile things that collapse without a constant stream of artificially cheap inputs — which sounds more “left” than even what most on the Left would argue today.

Up here in AK we had some state and local legislators who had been accused of corruption but hadn’t been charged or anything. They took to wearing ball caps around the state capitol saying “corrupt bastards club.” Funnily enough it turns out several of them ended up getting convicted by the Feds for illegal acts like taking bribes. One particular douche canoe, my former state rep, was caught on tape being bribed with 20’s from a rich oil guys pocket. He was a crook and pitifully small time. Whether that makes them corrupt or if they were actually bastards is still a question.

The local politicians pretty much all self-identify as both conservative and Republican. How they behave when it comes time to legislate may vary from the ideals they offer for public consumption. This sort of thing, however, is hardly limited to either local politics or any span of the political continuum.

What I wonder is — the cities compete with one another in the race to the bottom. The businesses which they compete to attract are inherently local. A business can say to Lancaster, just as Costco did in the setup story, “Hey, Palmdale is offering us X if we move there. We’re gonna take it, unless you do Y for us before Z date.” Is Lancaster corrupt for putting Y on the table in that case? Is Palmdale corrupt for offering X to start the process? Is the business corrupt for comparing — or even soliciting — these sorts of profit-enlarging options? Personally, I have a hard time assigning a high degree of moral blame to a for-profit business that complies with the law, and a harder time assigning moral blame to a municipality that seeks to attract jobs and tax revenues. The whole dynamic is unattractive, to be sure, but I don’t think any actor within such a dynamic is necessarily acting in bad faith.

If there were not competing jurisdictions to offer varying plans, would this sort of thing still happen? In very large unitary cities (e.g., Los Angeles) an inherently local sort of business (like a retail store) has fewer options, and local governments tend to be less deferential to private business with respect to these kinds of deals.

I would agree with you that there is no moral failing in cities (or states) using such tactics to lure businesses.

On the other hand, I would argue it’s important not to fall into the trap of believing that certain cities or states are “job creators” by doing so – at least on a macro level.

One would assume that they still get local sales tax revenue, and they still get employment, so cities get a benefit out of these sorts of things.

So it’s a race “downwards”, but I don’t necessarily know that the endpoint is “the bottom”.

I don’t necessarily have a problem with these sorts of negotiations as long as they’re legitimately in the best interests of the local community. There’s a lot of sludgewater to deal with down there, though.

A “race to the bottom” might in some cases be characterized as “market forces at work achieving equilibrium.”

Yes, I’m well aware a cashier working for one cent over the minimum possible wage they’ll take at their most desperate is a horrible distortion of the free market.

My problem is not with city A offering lower taxes than city B, it’s when they carve out tax breaks for specific businesses or industries. Taxes should be applied evenly to all. If city A wants to attract businesses, it should lower it’s overall corporate tax rate or be able to demonstrate how it’s use of corporate taxes creates a place companies want to do business in.

People assume it’s always a race to the bottom, when it isn’t necessarily. If a city wasn’t busy handing out tax money for political favors to businesses, they’d have more available to manage the services the public expects of them.

Wow. This is a great post, Tim. I really appreciate the polish that went into it. I have a couple things to add and then some questions.

You rightly condemn HFCS as the poster-child for everything that’s wrong with the U.S. regulatory state right now. I’m surprised you didn’t also mention that HFCS has the highest correlation with the development of obesity and type-II diabetes of any known substance.

I more-or-less subscribe to the Ron Paul view on earmarks, which is that they stand in opposition to vague discretionary spending; i.e. all Federal funds should be earmarked. That Lessig (and you presumably as well) does not agree with this seems inconsistent with your idea that clearly-defined boundaries for what government is and isn’t allowed to do are the defender of the Republic.

I’m a firm believer as well that agents respond to incentives within the structure, they do so predictably, and if we don’t like what emerges, we have to change the structure (I might characterize this as a “Marxist positive” although I certainly don’t agree with the Marxist normative.) That is to say, your categorization of large concentrations of wealth and cronyism as epiphenomenal to some underlying structural problem is right on. I do not share your optimism, however, that restoring power to the states will go a long way to correct the problem. I think we need some social-cultural correction if we’re to get out of this mess.

> I think we need some social-cultural correction

> if we’re to get out of this mess.

I agree, we need that.

I’m not so sure that a more federated system of tax collection and disbursement won’t be better, though. The advantage of pushing a lot of the revenue collection and disbursement down the ladder is that there are still higher rungs on the ladder.

Right now, the MMS can be full of corrupt bastards and when that gets out they get rebranded and nobody goes to jail. If the MMS was actually largely at the state level, and the federal “MMS” was basically only an oversight board that provided audits to the states and convened a big meeting twice a year so that the individual state boards stayed on the same page, you’d have the communication and standard operations advantages of a larger organization while still making it so that the feds had the incentive to proper police the thing. It would also be harder to capture: you’d have to suborn regulators in multiple states. It would also be easier to uncover captured regulatory bodies.

Now, it might still be the case that nobody goes to jail, but at least the bad actors would be at worst screwing one state at a time, instead of all of the Gulf states at once.

Good point. Perhaps I’m looking at it a bit too much through the lense of a Massachusetts resident: Massachusetts is basically a (benevolent?) party dictatorship.

capturing regulators is easier the more local they get. people with money buy regulators, or the regulators disappear, just like the people on the wrong side of power.

Benzene is tasty… Benzene is good…

Kim,

You made a similar comment in a recent post, and I bore it firmly in mind as I explained the relationship of both motive and opportunity. Note that the claim is never that federalism and localism causes opportunity to diminish. Instead, it causes motive to diminish. In fact, it is because the opportunities are so diffuse that this in effect reduces the most important and dangerous kind of opportunity: the opportunity to purchase a lot of power in one place.

A nursing home only needs to buy its own regulators. Local or Federal, it matters not.

Perhaps this is some sort of economy of scale issue, wherein some industries would benefit from more local control, and others from more federal control.

(Link me back to your other post?)

And, the Federal government theoretically exists to ensure that the States do not fall prey to capture of regulatory power. The Federal government should exist to enforce contracts.

Kim,

Here’s the link: https://ordinary-times.com/blog/2011/10/30/can-the-occupy-movement-tackle-crony-capitalism/#comment-200156

I’ll again point to the recent court victory of the citizens of Los Alamitos. This was crony capitalism most foul, done in a small community. So no, making government smaller does not, by itself, eliminate or even reduce the opportunity for rent-seeking. But what it does mean is that the opportunities for redress are more accessible. If trash hauling service were handled at the state or, God forbid, federal level, it would have taken an army of attorneys to challenge the law. Moreover, the rent-seekers would have had much deeper pockets, meaning more vicious and costly and time-consuming litigation and appeals. This means it would have been impossible for a handful of citizens to seek redress, as in Los Alamitos: it would have taken hundreds of not thousands of litigants [well, maybe not THAT many], and/or an aggressive public relations campaign to raise funds to keep the litigation going.

Centralized government can only pretend at efficiency on the front end. When things go sidewise, there’s a saying about the bigger they are….

[Edited 12:46p -TK]

TK,

well, your argument holds up surprisingly well against blackmail. rather poorly among naked cash transactions though… it costs about the same to buy one representative at any level of the government, assuming all you need is a “friend”. Steady stream of $1000 will do ya all you need…

Breathing oxygen also has nearly a 100% occurrence in obese persons. I think we need to look into te correlation between oxygen consumption and obesity.

Good thing even epidemiology studies use control groups.

This is the part where you post a link.

Are you looking for a link wrt HFCS,

http://www.yaleruddcenter.org/newsletter/issue.aspx?id=3

or the methodologies of epidemiology studies,

http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/283/15/2008.full

Or the closest we can get without violating ethical standards and feeding humans something that may be dangerous?

http://www.foodpolitics.com/wp-content/uploads/HFCS_Rats_10.pdf

Nob, a hearty welcome to the League!

Regarding Obama’s Socialist’s leanings, I can tell you a few unmistakable incidents that point him leaning in this direction–just last Easter, he insisted all children receive the exact same number of eggs regardless of how many they find–this is an annuel event–the Easter Egg Roll– that takes place at the White House during Easter Week.

And just last year at Thanksgiving, there is a tradition that the president grants amnesty to ONE turkey however Obama looked into the backgrounds and history of ALL the turkeys and decided to chop the head off of the richest turkey, granting amnesty to the 200 or so turkeys left.

He also strongly favors removing labeling from all foods in order for the poor and down trodden to have the opportunity to eat like the rich.

There are many, many more, but you get the idea.

Uh-oh. What hath I wrought? Damn…not sure what I hit.

“That is to say, your categorization of large concentrations of wealth and cronyism as epiphenomenal to some underlying structural problem is right on. ”

So if the government were structured differently, Costco would not have coveted their neighbor’s land?

No, if the government were structured differently, Costco would still be coveting their neighbor’s land.

But is it the structure that would have prevented their success, or vigilant defense of the structure?

Meaning, suppose we had legal structures that declared that no ones property could be taken without due process.

Would that be enough? Or would that simply leave open the possibility that a powerful interest could persuade the City that “due process” means, “Me wants it”.

I don’t think Tim was saying that any laws were broken; the actions were duly legal, and constitutional.

So is there some structure that can successfully resist the attempts of powerful interests to circumvent it?

I don’t think I’m well-versed enough on the subject matter to weigh in here in detail (i.e. I don’t know what the town bylaws were, I’m not familiar with state law or federal law).

But, I think Tim has illustrated quite well here how governmental power was used at the final authority that allowed Costco to take over the 99-cent store’s lot.

Theoretically we have three layers of government that could and should put a stop to such behaviors, and, if we want such behaviors to stop, we need to change the rules of the game so they do as opposed to thinking that all of economic society is a battle to the death between government and corporations. Tim has illustrated quite well here how the worst corporate abuses are made with the government’s seal of approval. Since, the government belongs to us, and corporations don’t, the proper way to resolve the matter is by changing the structure through which corporations move.

To the contrary, many of the problems discussed in the piece, including Costco’s holding Lancaster hostage, are a result of ongoing violations of the Constitution’s limitations of government. The Progressive era beginning in the late 19th century had the idea that society could be made better through government. It began with social conservatives trying to preserve Victorian values by force of law, but was largely redefined by the New Deal. Today, legislators like Nancy Pelosi scoff at the suggestion that there is any “serious question” that the Constitution still imposes limits on Congress, and legal elites scoff at Lochner v. New York as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time for the hubris of purporting to limit state power on the basis of some imagined and unenumerated “economic liberty.”

The hope that empowering government would deliver us from evil has left us without defense or recourse to the evil government works in its own right. “Power wins, not be being used, by by being there,” Schumpeter tells us. He was right. The tragedy in Lancaster ultimately was the mere fact that power was “there”—Costco knew it, and Lancaster knew it. Had the power not been there, the hostage-taker scenario could not have taken place.

To clarify, mine is a response to Liberty60.

OK, Tim, so as I have asked elsewhere, how do you propose to disempower government, when the Leviathan of private power is implacably opposed to you doing that?

Liberty60, I’m glad you asked. I propose restoring the Constitutional limits on government through the mechanism designed to do just that, i.e., the courts. This is the mission of the Federalist Society, and a worthy mission it is. In fact, stripped away of its perception as a bastion of The Right, there is probably much there that movements like Occupy could agree with.

For example, had the Supreme Court not abdicated its responsibility to enforce the “public use” clause of the Fifth Amendment, Costco would not have been able to hold Lancaster hostage. If the California Supreme Court had not abdicated its responsibility to enforce the state’s constitutional prohibitions on gifts and contracts without consideration, state and local governments could avoid some of its most onerous and unfair pension plans.

Finally, to cite an affirmative example of how the courts can serve as a backstop to thwart special interests, the Supreme Court’s finding that California’s prison system violates the Eighth Amendment will force state to undo some of the damage the powerful prison guards union has inflicted on the public. As Rich McKone, executive officer, California Coalition on Corrections, commented on another post, California “will save about $1 billion annually due to the Supreme Court decision. It could reduce prison costs by $2 billion annually if it were willing to limit prisons to Level III & IV inmates and place all the Level I & II inmates in county contract facilities where they belong. That, of course, will never even be considered because of CCPOA influence.”

They will never be considered, that is, unless there are legal and constitutional limits on what government is able to do—read: what special interests are able to buy.

Tim, sorry to sound like I am Red-baiting here, but your faith in governmental structure seems reminiscent of the socialists I used to argue with.

“If we only had the right system of laws and regulations”, they would say, “then we would have a truly just society.”

What governs the actions of the City of Lancaster?

Laws.

What governs the laws?

The Constitution and Supreme Court decisions.

What governs the Supreme Court decisions?

The President and the Senate appointments.

What governs the President and Senate?

Popular voting.

What governs popular voting?

PACs, think tanks, lobbyists, media-in other words, private interests such as….Costco.

There is no structure that you can erect that private power cannot defeat.

That is a feature of democracy, by the way. The laws and Constitution are whatever the voters decide they are.

Except in our world, all voters are not created equal. Some are much, much more equal than others.

I don’t think I can engage at quite that level of cynicism. That special interests (which includes not only the Costcos of the world, but the 99 Cent stores, too) would fund presidential candidates in hopes of getting Supreme Court appointments that would empty the meaning out of the Public Use clause in order to infuse unpredictability in property rights—all for the benefit of sometimes-Costco-but-sometimes-perhaps-99 Cents-depending-on-who-gets-the-jump—seems paranoid even by Dale Gribble standards.

Say what you will about a judge’s ideology, but I’ve not heard any serious person contend any Supreme Court justice is in the pocket of special interests. The most people argue is that there are issues concerning the appearance of partiality, or that the judge acts in line with his or her ideology. But not that any justice is economically motivated, as are many legislators. There’s a poll that I’m too lazy to find right now that shows the judiciary is the most trusted branch of government. This is particularly so when judges are appointed rather than elected.

Just to clarify-

I honestly believe Supreme Court Justices decide cases based on their most sincere understanding of the Constitution.

Now as for the Senators who placed them on the bench? The Presidents who nominate them?

Campaigns and lobbying are like advertising- why do people spend so much money on it? Because it works.

The private interests who funded the Senators didn’t know or predict the Kelo decision; but they knew and predicted the general judicial philosophies of the names that were picked out of the hat for nomination. As with gambling, you only need to shave the dice ever so slightly to tilt the odds in your favor.

Considering that the Kelo decision was “the Constitution says what it says it says”, I think we can hardly point to it as an example of the government putting business interests ahead of anything else. If you don’t like what happened in Kelo get your local legislatures to write better laws about what “public use” means. It’s not the responsibility of nine unelected life-term persons to run your world for you.

DD,

I think we’ve been through this before. Kelo did not hold that the Constitution “says what it says.” To the contrary, it followed a line of cases that holding that the constitutional standard the courts must apply is expressly different from what the Constitution says. I.e., the Constitution says: “public use.” The Court says: “public purpose.”

The reason the Constitution says anything at all is because those things are not appropriate to be left to legislatures. It is no answer to the problem of eminent domain abuse to advise people to make a stink at the next city council meeting. Such things were never meant to be decided democratically.

Christopher,

I’m not necessarily opposed to that approach to earmarks. Lessig and Schweizer point to the corruption in the earmark process, which I distill down to “opportunity” created by too much government control concentrated in too few lawmakers—e.g., Nancy Pelosi funneling $890 million for a San Francisco light rail project that will dramatically enhance the value of property she owns. Thus, I offer an antecedent proposal: remove from the federal government power over local transportation policy-making and other purely local issues that D.C. lawmakers have no business sticking their fingers in.

Thanks for clarifying that Tim.

“For example, Alaska—one of the 10 states for which independent expenditure data has been collected—is substantially more democratic than Congress. Alaska legislators represent on average fewer than 12,000 people and a share of about $760 million of the state’s total annual GDP.”

And yet Alaska is only middle of the pack when it comes to regulatory freedom, and has one of the highest rates of independent expenditure per capita; substantially higher than California at the other end of the legislative spectrum.

Iowa and Wisconsin do better, but Washington state gets a worse score from Mercatus than California on regulatory freedom, but has a less concentrated legislature than Michigan and Arizona, which both score well.

I’m not sure concentration of legislative power, at least as defined as few legislators/citizen or high GDP per legislator, is a useful predictor of anything.

Fnord,

Consider the three criteria we are examining here: democracy, political spending, and regulation. The first two of these things are “inputs”: Votes go in, certain laws and regulations and enforcement mechanisms come out. Money goes in, different kinds of laws and regulations and enforcement mechanisms come out.

True, the data I’ve referenced does not indicate a tight correlation between the inputs, i.e., concentrated legislatures and regulatory impact (though citizens-per-legislator do trend up with regulatory impact). That’s not directly what we’re examining here, however. We want to examine the “cause and effect” relationship of each of these two types of inputs with output.

My first set of charts might confuse this point since they compare the inputs, showing that as one type of input diminishes (i.e., as the people are represented by fewer and fewer legislators), this makes the other type of input more effective (i.e., political spending). In other words, political power hates a vacuum: taking power from the people gives it, directly or indirectly, to special interests.

The second set of charts shows the logical conclusion of what happens when power is transferred from the people to special interests: Regulatory burden increases. Granted, the Mercatus study does not tell us the design of the respective states’ regulatory burdens, i.e., whether they were crafted for the benefit of special interests. However, if you find Lessig and Schweizer as convincing as I do, it’s a safe assumption that special interests had a substantial say in crafting these policies, and are thus at least as much designed to retard market forces as to benefit the public.

I agree with you (and Lessig and Schweizer) that political spending leads to corrupt outcomes including increased unreasonable regulatory burden, as your final chart shows.

My point is I’m not sure that concentration of legislative power, as defined here, increases the effectiveness of political spending, and I don’t think you’ve shown that. Neither the direct measure of spending nor the resultant regulatory burden from the Mercatus data appear to correlate with legislative concentration. Obviously spending per legislator increases when there are fewer legislators; but that doesn’t mean more money is spent where power is concentrated, it just means the same money is split between fewer people. Spending per capita looks to be about the same, and that’s the measure connected to regulatory burden by your final chart.

This is relevant because you seem to be implying that corruption in the federal government is especially bad because of the even greater concentration of power there than in any state government.

All this is at first glance, looking at the a few of the states you mention in the post. You say citizens per legislator is correlated with regulatory burden, and I can’t say you’re wrong without looking more closely at the data, but I don’t see it looking at your post.

My last few posts have been far too harsh. I apologize for them (although not the thought behind them). I need a vacation from here, I think.

Once again, I’m sorry for the negative tone and abrasive attitude.

Perhaps it would be beneficial to seperate out legislative functions from budgetary functions. The first function sets the rules of conduct, which should change only slowly, and the other is day-to-day operations and spending. Yet we’ve traditionally used the same people to handle both, perhaps in part because the British Parliament (the historical seed Congress) wanted to rein in the king’s spending and was the only counterweight to his power, and so they took control of the purse, while they were also given lawmaking powers to end the traditional practice of rule by decree. The result was democracy and seperation of powers, with the legislative function seperated from the executive function, but we’ve still not seperated legislative powers from budgetary powers. The two functions are now so entertwined that it’s even hard for us to think of spending powers seperate from the legislature.

The result is that rent seekers who want changes in budgetary decisions, and the politicians they’re influencing, aren’t checked by the laws passed by some seperate branch because we’ve given them the convenience of one-stop shopping. No law passed by the people’s representatives to ensure fairness and equal treatment can long stand against government spending decisions because the politicians writing the budget also write the laws, not only letting them remove laws that inconvenience their quest for kickbacks, but giving all their spending decisions the force of law.

That’s really an odd situation, yet we’re so accustomed to it that it doesn’t strike us as odd. A company makes spending decisions all day long, as do individuals and government, yet we don’t think their day-to-day spending decisions are in any way related to labor laws, code-of-conduct policies, or property law. Unless engaged directly in government rent-seeking, legal chicanery, or maneuvers determined almost entirely by the regulatory environment, no major company uses its legal department for budgeting. Can anyone explain how expertise in Constitutional or criminal law is in anyway connected to cost accounting, strategic financial decision making, or whether the company should buy iMacs or Windows boxes? Yet in goverment, from local to federal, we saddled legislative bodies with both functions.

The result is a concentration of power and a conflict of interest. The same people who get to write the rules of social conduct, rules designed to ensure fairness and equal protection, are the same people whose spending potential is determined by tax revenues, and who are often rewarded (or re-elected) based on how they can redirect those revenues to favored parties.

Fascinating insights, Mr. T. I hadn’t thought of that angle. You’re right, it doesn’t strike me as odd, though it is a source of many problems. I’ll have to think on this more.

That would, in one big way, remove money from politics

Nice Post, Mr Kowal! a quick question though:

Doesnt Iowa give a lot of subsidies to its farmers? (Or are those federal subsidies)

This site seems like it would have the answers: http://farm.ewg.org/region.php?fips=19000.

I could not immediately find a breakdown between state and federal subsidies, though.

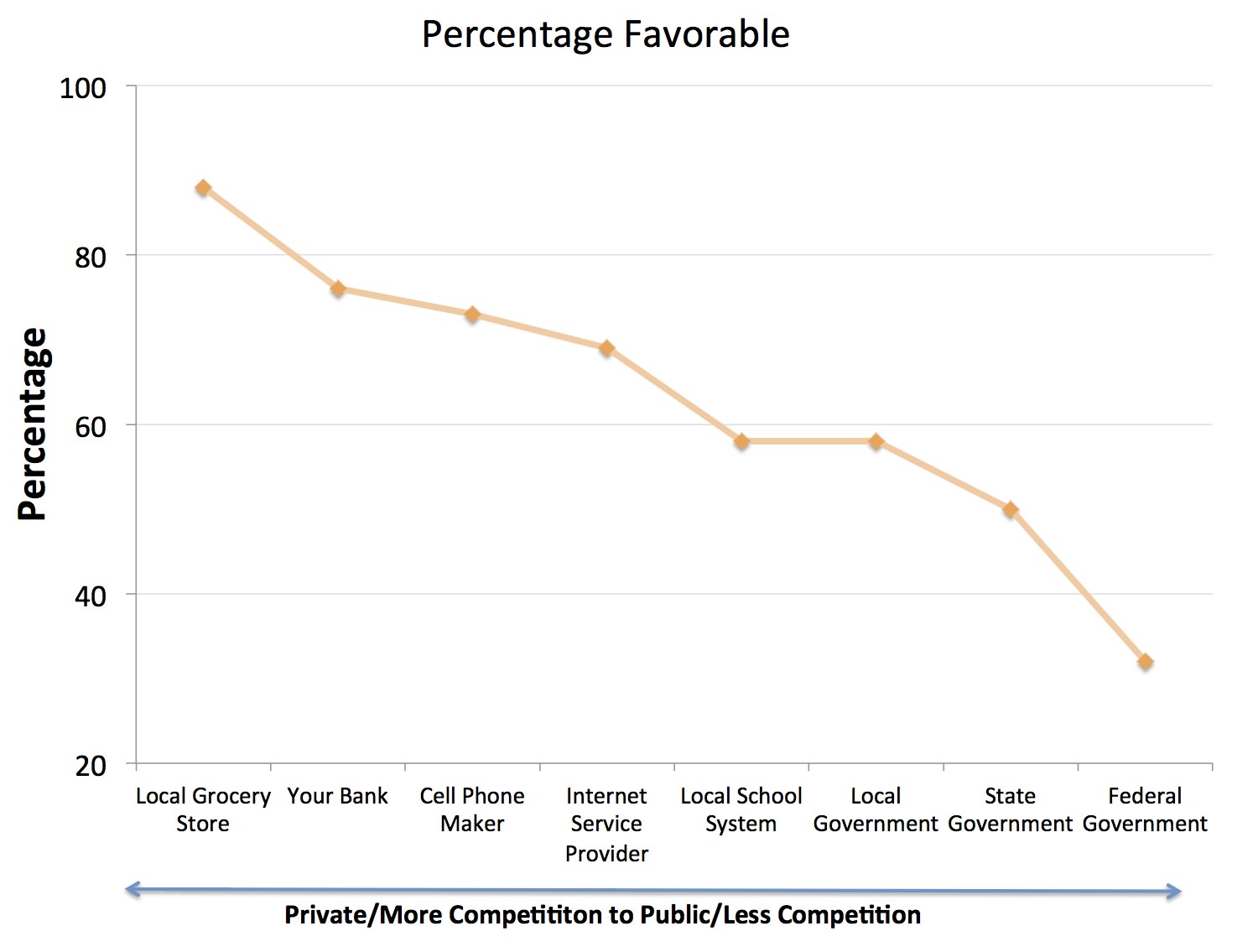

Emily Ekins at Reason posted these poll results today, quite relevant to the OP here. http://reason.com/poll/2011/12/21/american-favor-private-competitive-firms.

Let’s see if I can get the tags right to post the graph here:

I’m sorry, that’s sort of a silly graph. But I do love an official endorsement of public schools from Reason. 🙂

Please do note that the graph is not meant to suggest that local banks or grocery stores are in fact more competent than Congress, only that institutions appear less and less competent and trustworthy the further removed they are from the people.

Well, the infighting between district managers at Albertson’s isn’t covered on the nightly news and doesn’t mean your unemployment benefits won’t show up. I’d also guess this is largely the difference in opinion of local, state, and federal government. Local news doesn’t cover the insanity of state and local government, so your average person doesn’t know your Congressperson isn’t actually probably the least corrupt elected official you’re probably voting for each year. 🙂

Are we to assume the banks referred to are entirely locally owned? What is being defined as “your bank” in this?

My credit union is rather nice. Banks…my money will never touch the inside of one ever again. They can’t seem to figure out how to make money without fishing us.

… fishing us is a FEATURE not a bug!

This is the sort of graph that proves that government should never be entrusted with important things like Medicare, much less national defense.

Now if we could just get Safeway to make cluster bombs!

BAE makes cluster bombs, government just delivers them to the ultimate customer (who doesn’t actually want them, but, like most government programs, they are getting them anyway).

Speaking of weapons, I just created a brand new political party–I have successfully fused the Libertarian Party with the Raelian Party–we now shall be called the, Liberaelian Party! Ah, truly a match made in Hell, er, ah, um..I mean Heaven. Just need to get Kuznicki and Rael to sit down and hash out all the details. I guarantee we’ll sweep ALL 50 states!

And I have chosen you, Mad Rocket Scientist to be our Sec. of Defense and get this damn impenetrable Star Wars missile shield finished once and for all! I’ve also chosen Blaise to be our energy czar–he will be a one-man wind farm with enough bloviating energy to bring our energy bills to ZERO! Forever!

Here’s a little riddle I just made up: What do Danny Ortega and “Prophet” Muhammad have in common? They’d both have to register as sex offenders if they moved to the United States! How crazy is this–they have bloody riots, killing hundreds because of a freaking beauty pageant, yet their “prophet” is going around knocking up 9-year old girls. Okay, with all due respect, the prophet married Aisha when she was 6 and with great discipline that he showed throughout his entire bloodthirsty life, waited until the maiden reached the ripe old age of 9–yes, NINE years old before deflowering her. Just incredible to think that millions of innocent human beings have been slaughtered because of this child-molesting creep who has brought nothing but suffering, misery and bloodshed to the human race.

I am proud to introduce one of our new leaders, Mr. Rael!

(Note the Swastika inside the Star of David-WTF?)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pmSIYrVAQAo&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jm_kiwcaCuA

It would be utterly unfair and cruel of me to not mention to the Atheists at the League that help is truly on the way–if you want it.

I have a short clip that will, in all likeliness, liberate you from your Atheism. Beware: your life will NEVER be the same!!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5GA9cn9PTnw&feature=endscreen&NR=1

Errrr… OK?

See–I told you this would catch on like wildfire! Just bought a bullhorn and am off to spread the word. And we’ll all fly around in ultralight trikes—just bought one for everyone at the LoOG!!

Look.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3fVOIdCNTs&feature=fvwp&NR=1

Madman, sorry– that previous link to ultralights was a mistake–I’m not into fixed-wing ultralights rather flexible ones, known as trikes.

I just bought 30 of them for the Leaguers–let’s all meet on the West Coast soon. I’ll be happy to give instruction to the intrepid flyers. Considering the Raelians will have us all flying around in flying saucers in the not too distant future, the trikes will be a piece of cake!

Here is the type of trike I bought. Damn, this going to be fun! Do you think we could get the Doc to be on standby just in case? Blaise might open fire on us with one of his machine guns if for no other reason than just to shoot be out of the sky. Oh well, that’s the risk Liberaelians must take-I still haven’t figured what the hell ourt message is–I’ll leave that to Tom–

Tom, are you in? AWESOME! Tod, I don’t even need to ask you–I’ve appointed you Squadron Commander!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C95Cb2ByHNA

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=19420M5g3Oo

I’m still learning from you, as I’m improving myself. I absolutely liked reading everything that is posted on your site.Keep the stories coming. I enjoyed it!

“Let us take back our city and make it Los Angeles governed by the people for the people”

YJ Draiman for Mayor – proposes a Los Angeles City government for the people by the people, let us take back our city, it is long overdue to listen and address the concerns of the people of Los Angeles. Implement fiscal responsibility; restore trust and integrity in our government. This starts from the Mayor on down to the rest of government officials.

We must stop wasting revenues and resources, implement efficiency and productivity. These are hard economic times; in order for us to survive, we must take immediate action and implement the necessary actions to lessen the impact.

This starts at the top – “Lead by example”, leadership starts the pattern and the rest will follow.

The peoples brigade for Honest government.

YJ Draiman for Mayor of Los Angeles 2013