I just got through listening to a lengthy series of lectures about ancient Rome. I enjoyed it very much, but I thought that it was incomplete. The lecturer ended with the obligatory discussion of “Why did Rome fall?” and left it at that — he did not provide a very deep analysis about the legacy of the Empire.

I just got through listening to a lengthy series of lectures about ancient Rome. I enjoyed it very much, but I thought that it was incomplete. The lecturer ended with the obligatory discussion of “Why did Rome fall?” and left it at that — he did not provide a very deep analysis about the legacy of the Empire.

If you think about it, the achievement of the Romans was exceptional. The legends say that Romulus founded Rome on April 21, 753 B.C. and we know that Byzantium fell on May 29, 1453, when the Venetians double-crossed their former patrons and allied with the Ottomans and breached the walls of Constantinople. A comparable achievement would be if the United States of America, which began its existence as a British colony at Jamestown, finally falls on July 19, 3811. I suppose to make the analogy complete, the original United States would have to fail first, and then an American extraterrestrial colony would have to endure for another thousand years afterwards; the point is that the Romans did quite well for themselves as a civilization and we should hope do equal their record.

If you think about it, the achievement of the Romans was exceptional. The legends say that Romulus founded Rome on April 21, 753 B.C. and we know that Byzantium fell on May 29, 1453, when the Venetians double-crossed their former patrons and allied with the Ottomans and breached the walls of Constantinople. A comparable achievement would be if the United States of America, which began its existence as a British colony at Jamestown, finally falls on July 19, 3811. I suppose to make the analogy complete, the original United States would have to fail first, and then an American extraterrestrial colony would have to endure for another thousand years afterwards; the point is that the Romans did quite well for themselves as a civilization and we should hope do equal their record.

So without further ado, I consider the ghosts of Rome, which are still with us today.

Christianity: Probably the biggest and most pervasive single bequest from Rome is the religion which took it over. Europe became Christian because the Romans were Christians, and the Romans were unabashed exporters of their culture. In particular, the Byzantines were always very religious and theological debates several times threatened civil war. Certainly not all of Rome was Christianized by the collapse of the Western Empire in 476, but by then the “civilized” world had been Roman for a century.

Christianity: Probably the biggest and most pervasive single bequest from Rome is the religion which took it over. Europe became Christian because the Romans were Christians, and the Romans were unabashed exporters of their culture. In particular, the Byzantines were always very religious and theological debates several times threatened civil war. Certainly not all of Rome was Christianized by the collapse of the Western Empire in 476, but by then the “civilized” world had been Roman for a century.

Rule of Law: I think this is even more important, although much more subtle, than Christianity. The rule of law over the rule of strong men was not a completely Roman innovation, but then again, neither was Christianity. Rome co-opted and transformed the idea that laws govern men, and created an empire built on that idea. Consuls, and later emperors, were subject to pre-existing rules and had to abide by them. Moreover, even when they were in a position to make the rules, they governed by way of altering the rules instead of simply dictating their desires. The Magna Charta had its roots in the Forum.

Rule of Law: I think this is even more important, although much more subtle, than Christianity. The rule of law over the rule of strong men was not a completely Roman innovation, but then again, neither was Christianity. Rome co-opted and transformed the idea that laws govern men, and created an empire built on that idea. Consuls, and later emperors, were subject to pre-existing rules and had to abide by them. Moreover, even when they were in a position to make the rules, they governed by way of altering the rules instead of simply dictating their desires. The Magna Charta had its roots in the Forum.

Divided Government: In particular, the Republican Romans were obsessively concerned with achieving good government, realizing the will of the citizenry, and combatting corruption by dividing the powers of government amongst multiple office-holders. Frequent elections and rotating offices, vetoes, and checks and balances were created through hundreds of years of political wrangling by the Conscript Fathers serving in the Senate (and elsewhere). We have a President, a Congress (itself divded into two houses) and an independent judiciary because the Framers of our Constitution learned from the example of the Romans.

Divided Government: In particular, the Republican Romans were obsessively concerned with achieving good government, realizing the will of the citizenry, and combatting corruption by dividing the powers of government amongst multiple office-holders. Frequent elections and rotating offices, vetoes, and checks and balances were created through hundreds of years of political wrangling by the Conscript Fathers serving in the Senate (and elsewhere). We have a President, a Congress (itself divded into two houses) and an independent judiciary because the Framers of our Constitution learned from the example of the Romans.

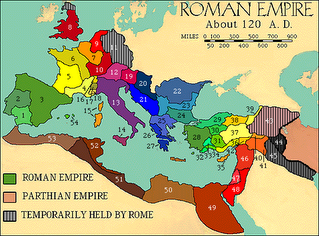

Federalism: Related to the idea of dividing government between multiple holders of office at the apex is the idea that government should be divided geographically. Roman government was initially created to govern a small city-state and the surrounding lands; as the lands under the sway of the Romans grew (explosively, during some phases of history), the solution was to establish local government to implement the will of the sovereign. Certainly, emperors and kings had governed remote lands through viceroys and other local officials before. The Romans, however, permitted their local governors a degree of flexibility, discretion and rule-making that had not been allowed previously, and the trend over the course of Roman history was for smaller and smaller political subdivisions. Click on the map to learn more about the various provinces of the empire.

Federalism: Related to the idea of dividing government between multiple holders of office at the apex is the idea that government should be divided geographically. Roman government was initially created to govern a small city-state and the surrounding lands; as the lands under the sway of the Romans grew (explosively, during some phases of history), the solution was to establish local government to implement the will of the sovereign. Certainly, emperors and kings had governed remote lands through viceroys and other local officials before. The Romans, however, permitted their local governors a degree of flexibility, discretion and rule-making that had not been allowed previously, and the trend over the course of Roman history was for smaller and smaller political subdivisions. Click on the map to learn more about the various provinces of the empire.

Violent Spectacle: The only complaint a Roman would have about modern professional football would be, much as modern rugby fans complain, that the players have too much armor and not enough personal risk. The visceral spectacle of athletic men (and sometimes women) clashing in violent and emotionally-charged ways is pure Rome. So too do the throngs of NASCAR fans, massing in numbers that dwarf football games, occupy the same seats as did the cheering masses at the Circus Maximus. The modern gladiators and chariot drivers do not often kill or even maim one another, but they please the crowd and enjoy rich rewards, both social and financial, for their toils and risks.

Violent Spectacle: The only complaint a Roman would have about modern professional football would be, much as modern rugby fans complain, that the players have too much armor and not enough personal risk. The visceral spectacle of athletic men (and sometimes women) clashing in violent and emotionally-charged ways is pure Rome. So too do the throngs of NASCAR fans, massing in numbers that dwarf football games, occupy the same seats as did the cheering masses at the Circus Maximus. The modern gladiators and chariot drivers do not often kill or even maim one another, but they please the crowd and enjoy rich rewards, both social and financial, for their toils and risks.

Civil Engineering: The Romans made a profession out of civil engineering, which is to say the building of large, civic structures with intelligence and precision. They did this through a system of private donations and public donations. There had really been very little done by way of public works construction other than religous structures and palaces. But the idea that the public should pay for the construction of buildings and other enduring structures for the benefit of the public has proven enduring. In particular, the aquarius (the engineers who built and maintained the elaborate network of aqueducts and tunnels that carried fresh water to the cities) enjoyed an honored and critical position in Roman society.

Civil Engineering: The Romans made a profession out of civil engineering, which is to say the building of large, civic structures with intelligence and precision. They did this through a system of private donations and public donations. There had really been very little done by way of public works construction other than religous structures and palaces. But the idea that the public should pay for the construction of buildings and other enduring structures for the benefit of the public has proven enduring. In particular, the aquarius (the engineers who built and maintained the elaborate network of aqueducts and tunnels that carried fresh water to the cities) enjoyed an honored and critical position in Roman society.

Women’s Property Rights: Women in Roman society, quite unlike most other ancient civilizations, could own their own property and resort to the legal process to protect it. A woman’s dowry remained her property, with her husband serving as a trustee for it. Along with this came an emphasis on educating women so that they could meaningfully control their property and otherwise serve a more effective supporting role for their families. While noble women were often married off to other noble men for dynastic and political reasons, both they and their less-privileged counterparts from lower segments of society had a significant measure of independence and prestige; and some managed to engage in business and commercial activity to an extent that a few became wealthy enough to privately endow public works projects, and inscriptions in their honor survive to this day.

Concrete: The Romans were better at this than anyone in history. Modern concrete, made from Portland cement and small gravel aggregate, is inferior to ancient Roman concrete, mixed from lime and ash recovered from Vesuvius. Roman concrete set and cured faster than its modern equivalent, and was every bit as strong. It lasts forever, too, as the still-extant skeletons of Roman roads, aqueducts, and buildings prove most impressively. The Romans used a form of rebar, too; the evidence of which can be seen in the hundreds of iron studs visible on the Colosseum even today.

Concrete: The Romans were better at this than anyone in history. Modern concrete, made from Portland cement and small gravel aggregate, is inferior to ancient Roman concrete, mixed from lime and ash recovered from Vesuvius. Roman concrete set and cured faster than its modern equivalent, and was every bit as strong. It lasts forever, too, as the still-extant skeletons of Roman roads, aqueducts, and buildings prove most impressively. The Romans used a form of rebar, too; the evidence of which can be seen in the hundreds of iron studs visible on the Colosseum even today.

Professional Military: The first armies were made from conscripts and commanded by officers drawn from the noble class. The Romans changed this by taking soldiers only from the body of the citizenry and drawing from both the noble and semi-noble classes of society for the officer corps. Beginning with a series of massive German invasions in the late second century B.C. and continuing through the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the Romans took all comers and made a career in the military an avenue for social and economic advancement for all segments of society. Even the leadership of the military became based on merit and ability rather than birth and wealth (although for the Romans, as for moderns, wealth and birth were always significant personal advantages). Our modern all-volunteer army, made up of a large number of people who seek to make their careers in the military, with its separate system of regimented and disciplined life, that seeks out and rewards merit, is the direct descendant of the legions.

Professional Military: The first armies were made from conscripts and commanded by officers drawn from the noble class. The Romans changed this by taking soldiers only from the body of the citizenry and drawing from both the noble and semi-noble classes of society for the officer corps. Beginning with a series of massive German invasions in the late second century B.C. and continuing through the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the Romans took all comers and made a career in the military an avenue for social and economic advancement for all segments of society. Even the leadership of the military became based on merit and ability rather than birth and wealth (although for the Romans, as for moderns, wealth and birth were always significant personal advantages). Our modern all-volunteer army, made up of a large number of people who seek to make their careers in the military, with its separate system of regimented and disciplined life, that seeks out and rewards merit, is the direct descendant of the legions.

Universal Citizenship: Perhaps the Romans made citizenship universal to broaden the tax base, but along with it came the concept of universal rights of property ownership, entitlement to due process of law, and nationalism.

Empire of Europe: The vision of Europe unifed into a single polity has never vanished. It survived in the empire of Charlemange, the Holy Roman Empire, the Hapsburg kingdoms (particularly under Charles V), and the wars of Napoleon, Bismarck, and Hitler; and is finally knitting together on economic rather than military or religious grounds in the still-evolving European Union. The trappings of Roman imperialism survive, too; the king of Germany was called “Kaiser” (German for “Caesar”); the most popular name for currency in North Africa is the “dinar” (after the Roman denarius); eagles remain favored symbols of martial and national power; the months of the modern calendar are named after the Roman months — and indeed the modern calendar, with only a few modifications, was invented by none other than Julius Caesar.

Empire of Europe: The vision of Europe unifed into a single polity has never vanished. It survived in the empire of Charlemange, the Holy Roman Empire, the Hapsburg kingdoms (particularly under Charles V), and the wars of Napoleon, Bismarck, and Hitler; and is finally knitting together on economic rather than military or religious grounds in the still-evolving European Union. The trappings of Roman imperialism survive, too; the king of Germany was called “Kaiser” (German for “Caesar”); the most popular name for currency in North Africa is the “dinar” (after the Roman denarius); eagles remain favored symbols of martial and national power; the months of the modern calendar are named after the Roman months — and indeed the modern calendar, with only a few modifications, was invented by none other than Julius Caesar.

It is going too far to claim, as some historians do, that we are all Romans today. But it is not going too far at all to say that we are the heirs of the Empire. Very much of who and what we are today is because the Romans did what they did in classical and medieval times.