Lawyers write lots of letters. Some days it feels like that’s all I do. A lawyer friend of mine asked the other day how to close his letters, and another lawyer friend pointed out that the closings on lawyer letters struck him as odd when he read them literally; “very truly yours” was a phrase that struck him as nearly meaningless and he got my curiosity up about where that phrase came from.

Lawyers write lots of letters. Some days it feels like that’s all I do. A lawyer friend of mine asked the other day how to close his letters, and another lawyer friend pointed out that the closings on lawyer letters struck him as odd when he read them literally; “very truly yours” was a phrase that struck him as nearly meaningless and he got my curiosity up about where that phrase came from.

There are lots of rules for closing out general business letters as well as lawyer letters, like the rule that says use “Yours faithfully” when you don’t know the recipient and “Yours sincerely” when you do. I’m not at all certain that these rules are hard and fast or that grammar authorities have any consensus on the question of the best way to close a professional letter. But “Very Truly Yours” is a valediction that is used almost exclusively by attorneys. Why is that? The etymology of the phrase (and other phrases using the word “yours”) traces back through the custom in Merry Olde England of signing off letters identifying the author as the “servant” of the addressee, even in cases where the letter was intended as an insult.

This seems to go back to medieval England when pretty much the only things written down at all were either legal or ecclesiastical in nature, and so all writings ended either with an “Amen” or some other invocation of God, an affirmation that the writing was authorized by the King, or with some supplication to the correspondent because the contents of the letter were a petition or some other kind of request for a favor.

So, the custom of medieval correspondents explaining why they ought to be given the favor that they requested traced back to the relationship of a vassal to a lord, which was ostensibly a relationship of a contractual exchange of services. The vassal should be given a favor because he is the vassal; the lord is supposed to render services of protection to the vassal, and thus both are servants of one another and that is why each should do what the other says. (In reality, of course, the vassal begs the lord for something which was either given or not, and the vassal took what he got and liked it.)

This evolved into lawyers petitioning judges and royalty for favors, and they kept the custom of reminding their correspondent that they (the lawyers) were the humble servants of the king and the court, and so it worked its way into polite written exchanges. One might imagine a note reading something like this resulting from this tradition:

Dear Mr. Burr,

Your Grave Insults to my Honour have not gone unnoticed and this brand of Knavery most Foul shall not go without ƒuitable response. I today demand an Immediate and most forthright Apologie in retraction of ye remarks, as ƒhould befit a proper gent. of true name, that which ye have disproven yourƒelf extant in the estimation of the better folk of New Yorke.

Failing to have recd. from you by Tuesday next your Apologie, I shall await ye arrival upon the Jersey banks of the ƒhore of the Hudson River at daybrk. on ye Friday, to resolve this Affair of Honour with the implement duello of your choice, as the Gentleman’s Right ƒhall then be yours.

I remain your most obedient and humble servant,

Alexander Hamilton.

(Obviously, the letter is fictional; Hamilton’s challenge to Burr was delivered orally, and through proxies, as was the custom of the day.) But you get the idea; no gentleman worthy of the name would have closed a letter to another without begging to be the “Most True Servant” of his correspondent. The servile phrasing of the valediction here would have seemed entirely customary despite the aggressive tone of the preceding portions of the letter. But from a closing like “I beg to remain your true and humble servant” the phrase would have been shortened to something like “I remain your true and loyal servant” to “Your true servant,” to “Yours truly.”

Even today, subjects of the British Royal Family are requested, for sake of politesse and etiquette, to address most members of the Royal Family in writing with the now-obviously similar phrase “Yours Very Truly,” with the exception of the Queen, of whom you must “remain” Her Majesty’s “faithful and obedient servant.”

In modern professional writing, a letter requires a closing of some kind to indicate to the reader that the content of the letter is complete. By custom and tradition, this comes before the signature of the author, which is given to verify the origin of the letter. Certainly, a closing must be complimentary rather than insulting or sarcastic in professional use; you can’t end the letter with something that leaves a bad taste in the reader’s mouth. And a professional valediction is of necessity cool in tone, as the letter is not being written in general to express friendship or warm feelings, but rather to accomplish some kind of professional purpose.

Now, for some reason, “Sincerely” seems to not be used (at least by attorneys) as its literal meaning is thought unnecessary – if you weren’t sincere about what you just wrote, why did you go to the trouble of writing it? But that logic doesn’t hold up when considering what “Very Truly Yours” really means. So I like “Sincerely.” When I am writing a lawyer from the law firm of Condescending, Stubborn, Foolhardy & Arrogant, LLP, to tell him that I’ve had it with his hide-the-ball negotiation tactics and filed suit against his obstinate client instead, I am in no way making myself that attorney’s “servant” – I am taking what I want from his client through the compulsory process of the courts, which is pretty close to the opposite of what you would expect from a “faithful and obedient servant.” I suppose “Very Truly Yours” is perfectly fine, but I’ve come to use “Sincerely” more often than “Very Truly Yours.” I’d prefer to be thought of as redundant rather than obsequious.

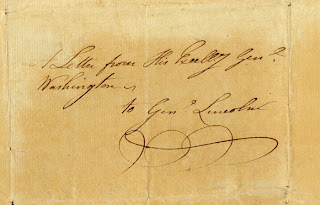

Your most obt Servt G. Washington