In medieval royal courts, the jester’s job was to amuse the courtiers, and to that end, the jester was given great license to speak truths that no one else would say. If the king had a gigantic wart on his forehead or the queen snored during religious ceremonies, the jester could speak truth to power and make a joke out of it. This actually served an important role of pointing out how the masters of the realm could improve themselves, and in the pointed jokes and asides from the court jester real flaws in policy could be identified.

In medieval royal courts, the jester’s job was to amuse the courtiers, and to that end, the jester was given great license to speak truths that no one else would say. If the king had a gigantic wart on his forehead or the queen snored during religious ceremonies, the jester could speak truth to power and make a joke out of it. This actually served an important role of pointing out how the masters of the realm could improve themselves, and in the pointed jokes and asides from the court jester real flaws in policy could be identified.

In Scandinavian countries, a public position called “ombudsman” evolved over time as local republican governments gradually supplanted feudal rule. The ombudsman’s job was to be a conduit between the people in power who made decisions and the people who were not in power, who were affected by those decisions. Not quite an advocate for the little guy, but also not a crony of the people calling the shots, the ombudsman could be a trusted source of information and ideas by giving voice to the concerns of the public rather than those of the elite — and if those in power chose to use him in such a fashion, a valuable tool for making decisions which were both popular and effective.

After the Watergate scandal in the early 1970’s, America created its own, somewhat less colorful way of finding people whose job it would be to speak truth to power. Independent counsel were chartered to wield the power of the government but not be directly accountable to the executives and legislators they were investigating. Independent bodies of prosecutorial agencies were created to provide independent opinions and advice about what government officials were doing. While not as humorous as court jesters, and not as steady as the ombusdmen, these people (lawyers, mostly) fulfill a critical role of telling our leaders when they are overstepping the boundaries of their power.

It is with great apprehension, therefore, that I read today a linked article from The Mighty Middle that President Bush and Attorney General Gonzales have denied security clearances for attorneys from the U.S. Justice Department who were trying to investigate the legality of the National Security Agency’s use of warrantless wiretaps. In other words, the White House is going to not allow these people to gather enough information to render an opinion about whether the program is legal or not — and then turn around and say that no one but they are qualified to issue such an opinion because only they have access to the information. The circularity of the argument is breathtaking.

So is its imperiousness. Bush simply does not want to hear people say what ought to be intuitively obvious to a first-year law student — the government eavesdropping on someone’s conversation requires a warrant. He also does not want to be reminded of the breathtaking ease with which those warrants are available to investigators. To do so would be to admit that he was wrong and that he walked all over the Constitution, even if it was for the noble cause of trying to protect America from attack.

Americans want to be safe and secure. But we should not be willing to stop being Americans. America is a country of divided government, a country of checks and balances, a country where there is transparency to decision-making, a country where civil liberties are cherished, and a country where our leaders are held accountable for their actions. This, however, is not George Bush’s vision of America.

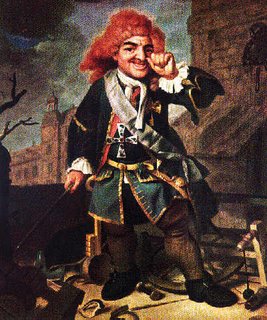

I am reminded of another historical anecdote. Roman generals would return to Rome after a successful military campaign and ride their chariots in parade down the streets of the city to the Forum, preceded by their soldiers and the spoils of war on display for the adoring crowds. Tens of thousands of Romans would cheer on the general, celebrating his triumph, as he was dressed in full military regalia and wore red paint on his face, which made him a living symbol of Mars, the god of war. The general’s political popularity and power would never be so great as they were during his triumphal parade. But here’s the rub. The triumph, and all the glory and power and everything else that went along with the pinnacle of this man’s career and probably the best moment of his life, had one inflexible condition. There had to be three men in the chariot — the triumphing general, the driver, and a third man, traditionally a dwarf or what we would today call a “little person.” The dwarf’s job was to periodically stand up and whisper in the general’s ear: “You are only a man.” See, the general had to be reminded that although he looked like a god, and the crowds worshipped him like a god, he wasn’t. He was only a man.

George Bush just silenced and cut off at the knees the best chance he had of getting a friendly but firm push back towards the right side of the Constitution — a push his administration desperately needs. What this man needs, clearly, is a dwarf.

“W” has fired everyone who has ever tried to tell him the truth or even a differing opinion.